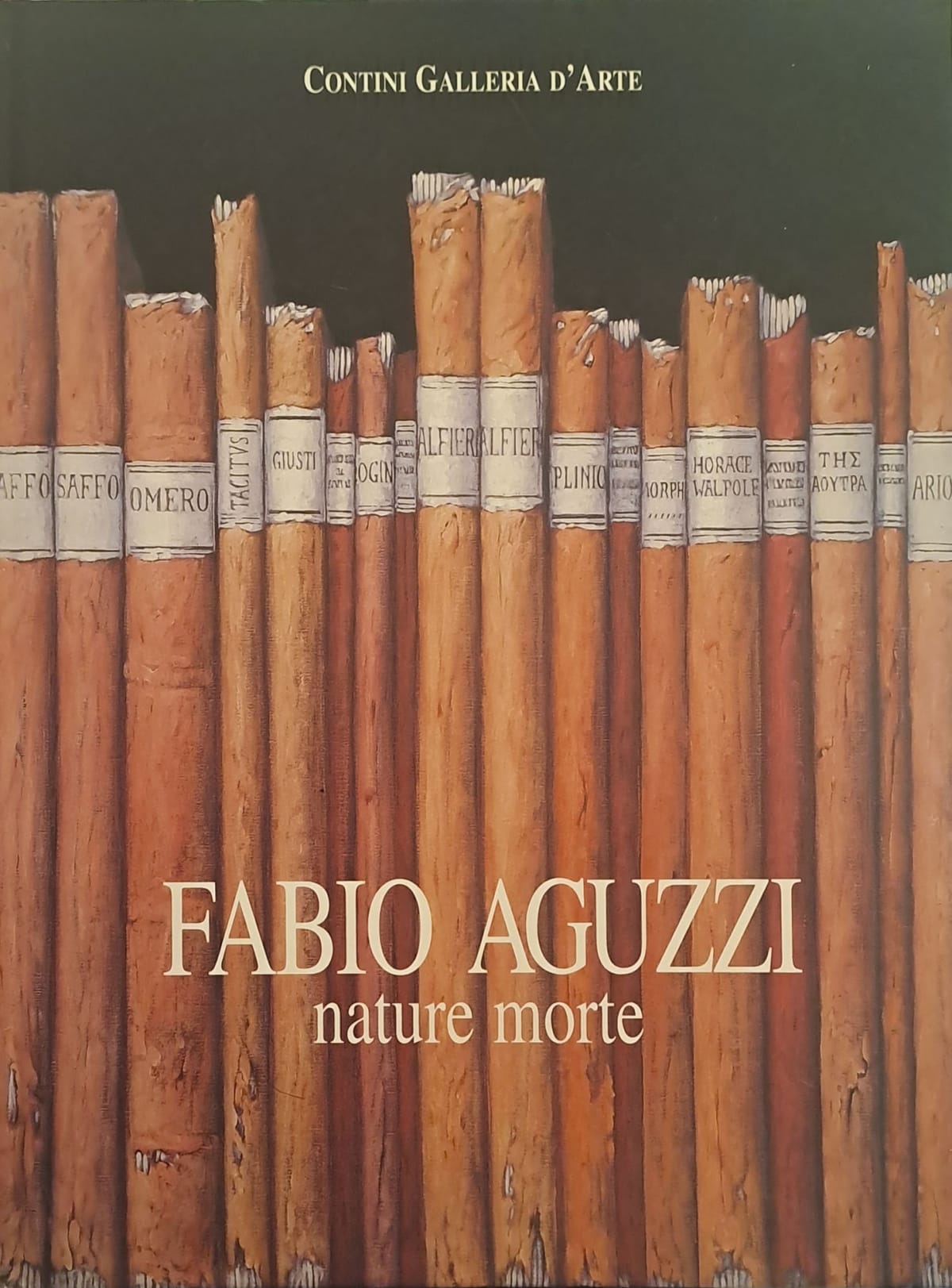

Fabio Aguzzi: Nature Morte, Cortina d'Ampezzo

The weave of language

When one looks at the works of Fabio Aguzzi there jumps to the eye, in immediacy of perception, a persistent research of symmetrical "framing". His objects, whether they be baskets or wicker chairs, ceramic jugs or plastic toys, take up the entire surface of the canvas and so the whole visual field, with the exception of a kind of lateral "'margining" which, however, is equal and mirrored on the right and left. This is also true with regards to the vertical development of the images, where Aguzzi tries once again to produce even gaps; we find proof of this in the fact that even when the object tends to "fly off* towards the upper border, the artist immediately employs a strategic cloth, a swath of fabric or a garment which rests on the lower plane and so recompresses 'democratically`'the whole of the distribution on the surface. The result of this is a sort of "horror vacui" a filling of space, an exclusiveness of the object, centered in the sights of a kind of an imaginary zoom lense. From this premise, one could easily reach the conclusion that Aguzzi's intention is to adhere to reality, gliding across it so closely that the eye joins with the forms depieted. However, you realize that this is all a deception. In fact, the painter chooses to reproduce materials like woven straw, wicker _and others which in their own right propose themselves as the result of a thread-like weave of curved and broken lines. If we then observed Venetian landscapes, we would realize that all the architectural styles of this city, from the most to the least notable, are reproduced in paintings with the same technique: brushstrokes woven or at any rate thread- like, after the manner of secessionist disivionism spanning two centuries, which in this case is employed in a sort of

automatism of signs. We then see that not only is the naturalistic hypothesis deceptive, but further, that precisely in this "'deception" there inscribes itself the poetic sense of the

artist, whose predecessors are all traceable, non one side in the hallucinatory spirit typical of Flemish culture and on the other in the infinite faceting metaphysical or surreal culture. The objects depicted by Aguzzi are in fact ghosts, pure and simple weavings of narrow brushstrokes in the firm grip of method. Reality, persistently hunted and captured, in the end evaporates in absence, in the pure logic of language. A sign among other signs, this absence, in perceft formal harmony, refuses the tangibility of forms.

Giorgio Cortenova